I remember vividly my first journey to Afghanistan in early 2002, not long after the removal of the Taliban. The late writer and journalist Steve Masty and I had persuaded two contacts from Afghan anti-Soviet Resistance days to drive us to Kabul, so we set out in their rusty old car over the Khyber Pass. You could tell how dangerous they thought it was by what they did with the machine gun. First it was in the boot, then hung over the back of the seat, then gripped firmly by hand. In the event it was the road, full of potholes deeper than a man, that almost killed us. We were hit by a truck that sliced off part of the front, including one of the headlights. The night-time climb up the steep road into Kabul in pouring rain with zero visibility was not a pleasant experience.

We got there to find a wrecked city. Nothing functioned. There was no central bank, no budget, no tax system, no electricity, no phone system, no decent roads. Not so much a failed state as no state at all. I took part in two World Bank missions in the following months to analyse what needed to be done. A vast quantity of investment was required, but unfortunately it was not forthcoming. Washington was distracted by planning and implementing its war in Iraq, and then by trying to deal with the chaos they had unleashed. While President Bush paid lip service to nation-building in Afghanistan, in practice the US focused on counter-terrorism while spending next to nothing on reconstruction. Their idea was to delegate this to European allies and the usual alphabet soup of multilateral donor bureaucracies.

This was a bad mistake. For these organisations procedure is much more important than achieving results, and their incompetence and dilatory approach was the last thing that was needed. Although moving somewhat faster, European bilateral donors like Britain did not put in the resources that were required. For the first three years the Blair government spent less than £100m per annum on bilateral aid to Afghanistan, less than that allocated to Tanzania. Unlike Tanzania, which has the routine problems of a developing country, everything in Afghanistan needed to be rebuilt. The task was of an entirely different order.

Critically, little was done to create a functioning army and police force. Training in this area was the responsibility of Britain, Germany and the UN, who, in the words of one US official, ‘wasted five years doing essentially nothing’. In the absence of security, life in the Afghan provinces was blighted by lawlessness and corruption and the average Afghan could not see concrete improvements in their life – there was still no electricity or proper roads.

Sipping their lattes in smart Kabul cafes, the complacent donor bureaucrats failed to understand the reality on the ground and it is not surprising that the Taliban managed to gain enough support to start a military campaign. In the absence of an Afghan army or police foreign troops were deployed with scant knowledge of local conditions. This poured petrol onto the flames.

Realising their error, the US started spending significant sums from around 2007, but by then it was already too late. The US spent $132 billion on Afghan reconstruction, but almost all of it after 2007 and two thirds allocated to the army and police. Had a proper effort been made from the start, many lives and a great deal of money could have been saved.

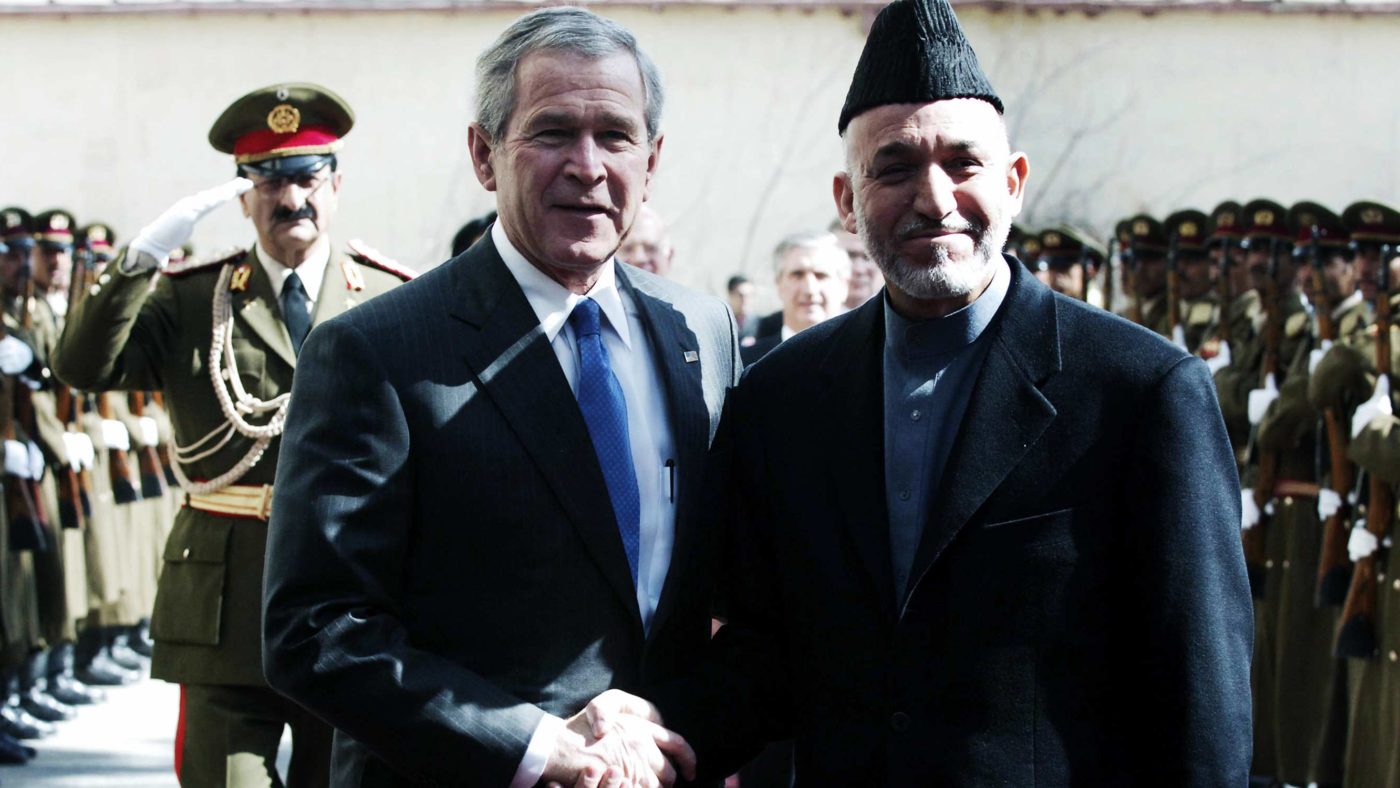

Early decisions on the new political system did not help, with power being concentrated in the hands of one man, the president. The first occupant of this post, Hamid Karzai, was a wily political operator but a hesitant leader. The second, Ashraf Ghani, was a menace. Formerly a World Bank bureaucrat, he is a know-it-all with a grossly inflated ego. I remember presenting a carefully designed plan to him around 2003/4 on how to privatise and get investment into the various decaying state enterprises that littered the country. He was very angry that this would take not two but at least six months – the minimum time for doing this properly – and rejected the advice. Needless to say, the enterprises never got privatised.

His period in office has been characterised by his arrogance and offensiveness, not least when he managed to insult Afghanistan’s entire Uzbek population by denigrating their history. But Ghani’s worst feature by far was his insistence on micro-management. He was well known for going through thousand-page procurement documents in meetings and finding one page with technical specifications he didn’t agree with. He was unable to assemble a good team because he wanted to take all decisions himself, including running the war against the Taliban. He disempowered every minister by promoting junior desk jockeys to deputy minister and then ran each ministry from the presidential palace by dictating detailed instructions to his placemen.

Given all that, it’s hardly surprising that few wanted to risk their lives defending the Ghani administration, and that he had to flee the country with his tail between his legs.

By failing to grasp the scale of the task and failing to move with the urgency that was absolutely required Bush and his allies, Tony Blair included, fatally undermined the prospects of stabilising Afghanistan. Even so, with a minimal contribution of Western troops an unsatisfactory status quo could have been maintained for years. It took a particularly high level of stupidity on the part of Present Biden to pull all troops out on a strict timetable and hand the country on a plate to the Taliban.

If we are to salvage anything at all from this dreadful situation and help the Afghans who have helped us, we now need a far better quality of decision-making from our leaders and those who advise them.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.